The feature serves as an alternative to Google Search and Microsoft Bing. However, while the tech giants battle over how and where we search for information online, I believe we should be cautious about jumping on board with OpenAI’s new functionality.

The competition between search engines and language models is intense, and OpenAI has acquired the domain chat.com, which redirects directly to ChatGPT. Their goal might be to create dependency on their service by elevating “chat” to a synonym for AI, much like how we use “Googling” as a verb. Many students equate ChatGPT with AI, which poses a challenge we must address in education—AI is more than chat.

In schools, students are taught how to conduct information searches effectively using search strategies and source criticism. However, this approach is far from perfect. Not all students progress to the second page of search results, and if the information isn’t at the top of the search, they often assume it doesn’t exist. Additionally, advertisements influence search results, and AI has started summarizing content for users.

But is moving the search function directly into the language model the solution? In this post, I will explore some of the opportunities and challenges I see.

What is ChatGPT Search?

In the paid version of ChatGPT, users can now access a small icon that allows ChatGPT to search the web. Below, you can watch a short video in which OpenAI demonstrates new possibilities.

Currently, the feature is only available to paying users, but it will eventually be rolled out to all ChatGPT users.

A New Dynamic Search Experience

Language models have been widely criticized for fabricating sources, and in our presentations, we always include slides to highlight this issue. There’s a significant difference between the free and paid versions of ChatGPT in this regard. The free version hallucinates to such an extent that it’s almost unusable, which, again, contributes to inequality among students.

Since ChatGPT Search can retrieve information online, like Microsoft Copilot and Google Gemini, OpenAI effectively enables a dynamic user search experience. This could make searches more precise and faster and provide better results based on user preferences and prior searches. If there are sites users dislike, the model’s memory can be updated to exclude those sources from future searches.

However, all of this contributes to creating an echo chamber, where we are continually presented with information that we and the language model deem correct. The model risks reinforcing the user’s opinions, and we might lose some of the serendipitous discoveries that come with traditional searches, such as finding interesting new sources on page four of search results. AI in search engines and language models could function like blinders, preventing us from seeing the bigger picture. The risk is that we may also become overly dependent on AI systems in ways that weaken our critical thinking skills.

The Quality of Sources

The big question, however, is how OpenAI handles the quality and reliability of the sources it presents to users. Currently, we’re accustomed to refined algorithms from Google and Microsoft selecting results for us, with search engine optimization often determining what appears at the top. Right now, it’s not transparent how results are selected in ChatGPT Search, though we assume it’s done ethically. For traditional search engines, ads are marked, distinguishing them from organic results.

In my ChatGPT Search tests, the source selection seems pretty reasonable, but I have also encountered questionable sources. For instance, sites like AiPedia, Elblog.pl, and Undetectable AI. Here’s an example where ChatGPT Search provided a correct answer, but the source was an AI-generated page on a dubious site:

Eksempel på en række tvivlsomme kilder.

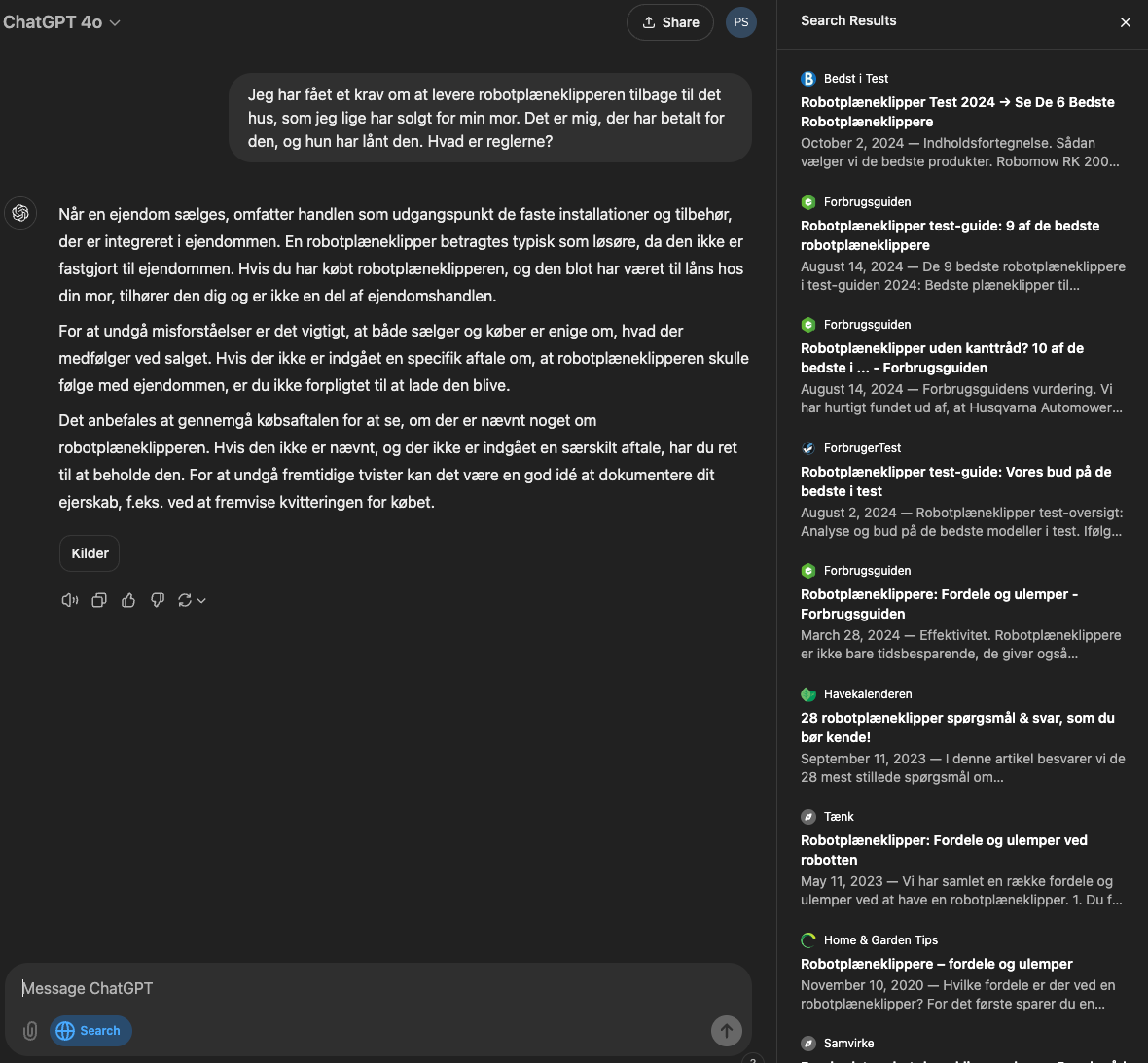

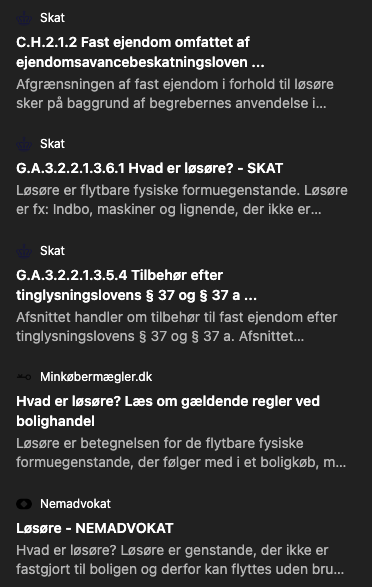

Generally, it is often unclear how sources are used, which creates a false sense of security when conducting searches. In one case, I asked about the requirements for personal property in a real estate transaction. The challenge was that sources were provided, but all of them were reviews of robotic lawnmowers—none of which had anything to do with the question I asked myself. While an answer was generated, the sources were not used, even though ChatGPT’s content appeared to be derived from them.

It wasn’t until several attempts later that I received sources from Skat (the Danish tax authority) and Minkøbermægler.dk. Additionally, it seemed that the term “robotic lawnmower” was weighted more heavily than “house,” “requirements,” and “rules,” which might explain the initial response. However, this also means that sources are only used correctly when the query is phrased in a particular way.

Should the Author or an AI Model Handle Summarization and Selection? Both approaches have advantages and disadvantages, each carrying risks of manipulation, errors, and omissions. In my tests of ChatGPT Search, I encountered many questionable sources, including small AI-generated blogs, dead links, outdated information, and content hidden behind paywalls.

ChatGPT Search Distills Content

OpenAI collaborates with established sources like Associated Press, Axel Springer, Condé Nast, Dotdash Meredith, Financial Times, GEDI, Hearst, Le Monde, News Corp, Prisa (El País), Reuters, The Atlantic, Time, and Vox Media, suggesting a positive step for information quality. Websites can allow OpenAI to use their content if they wish to contribute, or they can block AI access altogether.

However, how topics outside these knowledge bases are handled or what happens with material in other languages remains unclear. Many websites refuse language models access to their content, potentially skewing search results.

Unlike ChatGPT Search, traditional search engines display a list of results that users must navigate and evaluate themselves. ChatGPT Search, by contrast, rewrites and summarizes the results, presenting a cohesive answer with source references. This eliminates the need to visit the source, with no ads or other distractions interfering.

The Incentive to Publish Content Online

This dynamic raises questions about incentives to publish content online. If a website becomes merely a feed for language models, will creators lose motivation to produce high-quality material? Many may also lose ad revenue and, as a result, choose to block language models from accessing their content. Only large, established news outlets may be able to strike financial agreements with tech companies, potentially leading to a more polarized internet.

Your Prompt Shapes the Results

Another critical factor is how users phrase their queries. Even small changes in phrasing can lead to vastly different—and sometimes incorrect—responses from ChatGPT Search. In an educational context, this can be problematic if a student lacks the subject knowledge to critically evaluate the model’s answers or formulate an effective query. For example, a student writing an assignment on climate change might ask ChatGPT, “What are the causes of global warming?” The response could differ significantly from asking, “Which human activities contribute to the greenhouse effect?” Crafting the right question and assessing the answer requires substantial subject knowledge. If a student uncritically uses these AI-generated answers in their work, it could lead to incorrect conclusions and a lower quality of academic output.

Conclusion

OpenAI’s ChatGPT Search is likely the future of how we find information online. However, many unanswered questions remain about the quality and reliability of the sources presented to users. In education, students must learn to critically evaluate the information they find online—whether through traditional search engines or AI-driven tools like ChatGPT Search.

We must not be dazzled by the ease of access to information and forget to question the credibility and relevance of sources. The challenge becomes even more significant as AI blurs the lines between search results and training data.

In schools, we must stay informed about AI and search technology developments. We must ensure students gain the skills necessary to navigate a digital world where the boundaries between searching, summarizing, and AI-generated content are becoming increasingly fluid.

Sources