The rapid development of generative artificial intelligence (AI) has significantly impacted how we search for information. Google and OpenAI have each developed new search engines—Google AI Search (not yet available in the EU) and Search GPT. Both companies claim their technologies will fundamentally change how we find and process information. These tools promise to make knowledge access more straightforward and efficient by providing summarized answers with source references.

In a previous article on viden.ai, Per wrote the following:

“OpenAI’s ChatGPT Search is likely the future of how we will search for information online.”

This statement has sparked significant attention, as many academics reject the claim. The reality in high schools, however, is that students are increasingly embracing these new AI search engines. I’ve already seen examples of students who hardly use Google anymore—they ask ChatGPT Search instead and find it fantastic! And it doesn’t stop there. OpenAI now offers a search extension for the Google Chrome browser, allowing ChatGPT Search to become your new default search engine.

Challenges with AI Search Engines

When installing this extension, whether you are using ChatGPT Search or a regular search engine becomes unclear! Students will quickly forget how their search results are generated.

Below, you can see how OpenAI presents its AI features in the macOS desktop app. Notice how ChatGPT Search finds factual information without engaging in more profound source criticism.

Kilde: OpenAI

Although these new “search engines” appear sophisticated, they raise significant questions about the quality and reliability of the information they generate, the websites they access, and, most importantly—can we even consider this knowledge?

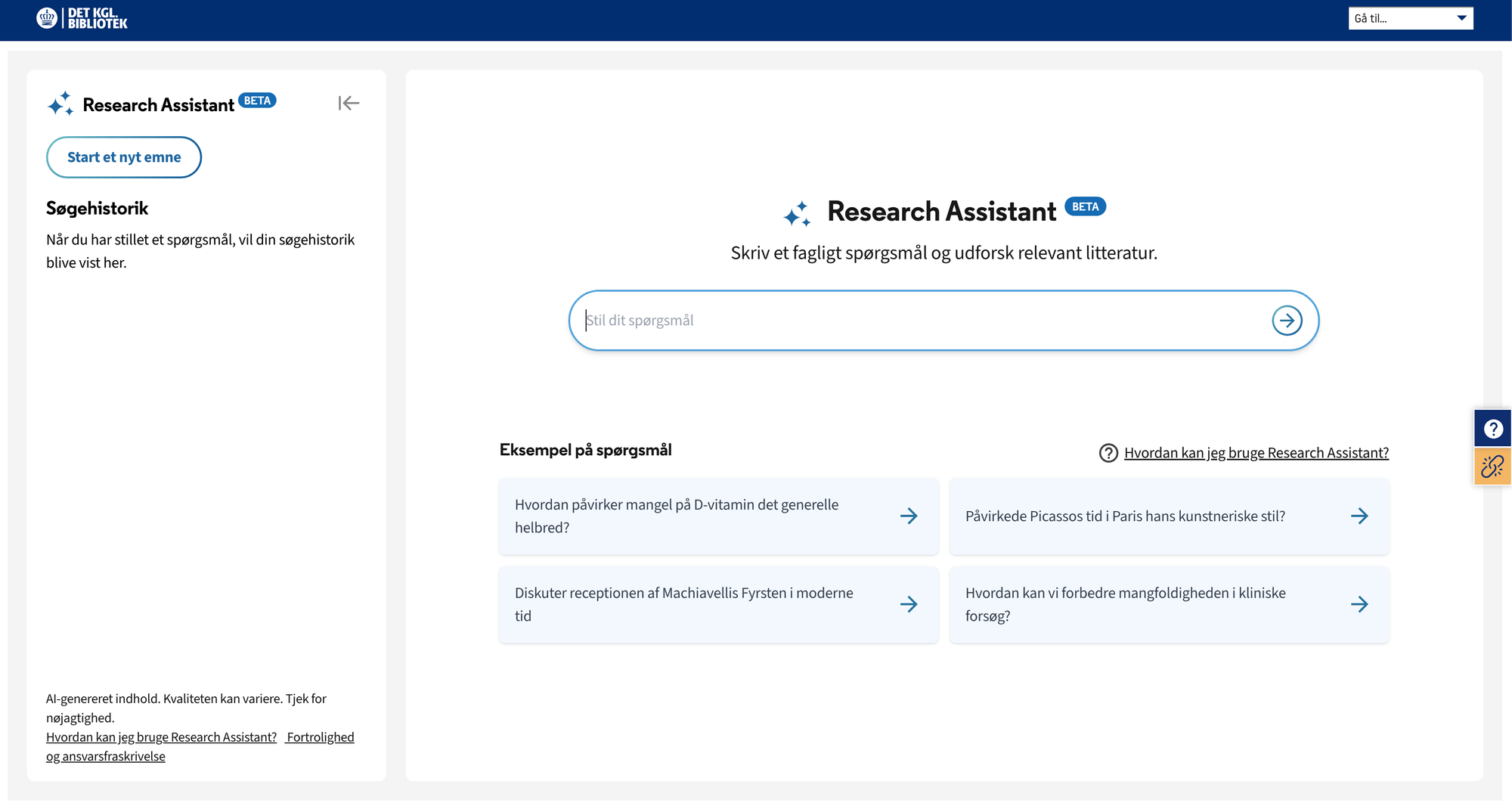

The Danish Royal Library has also launched a so-called “AI Research Assistant,” which works similarly. You ask a question and receive an answer based on five selected sources.

Your question is transformed into a query that the search engine interprets using a large language model (currently GPT-3.5). The search engine then identifies relevant documents, ranks them based on how well they answer the question, and generates a response using the five sources. Due to the nature of large language models, answers to the same question are not always identical. There may be more than one possible answer and various relevant resources. If you are dissatisfied with your answers, you can use the “Try Again” button.

The biggest challenge is that most students (and, more broadly, most people) cannot fully grasp the challenges and limitations of these technologies. They see them as a tremendous aid that can streamline our access to knowledge.

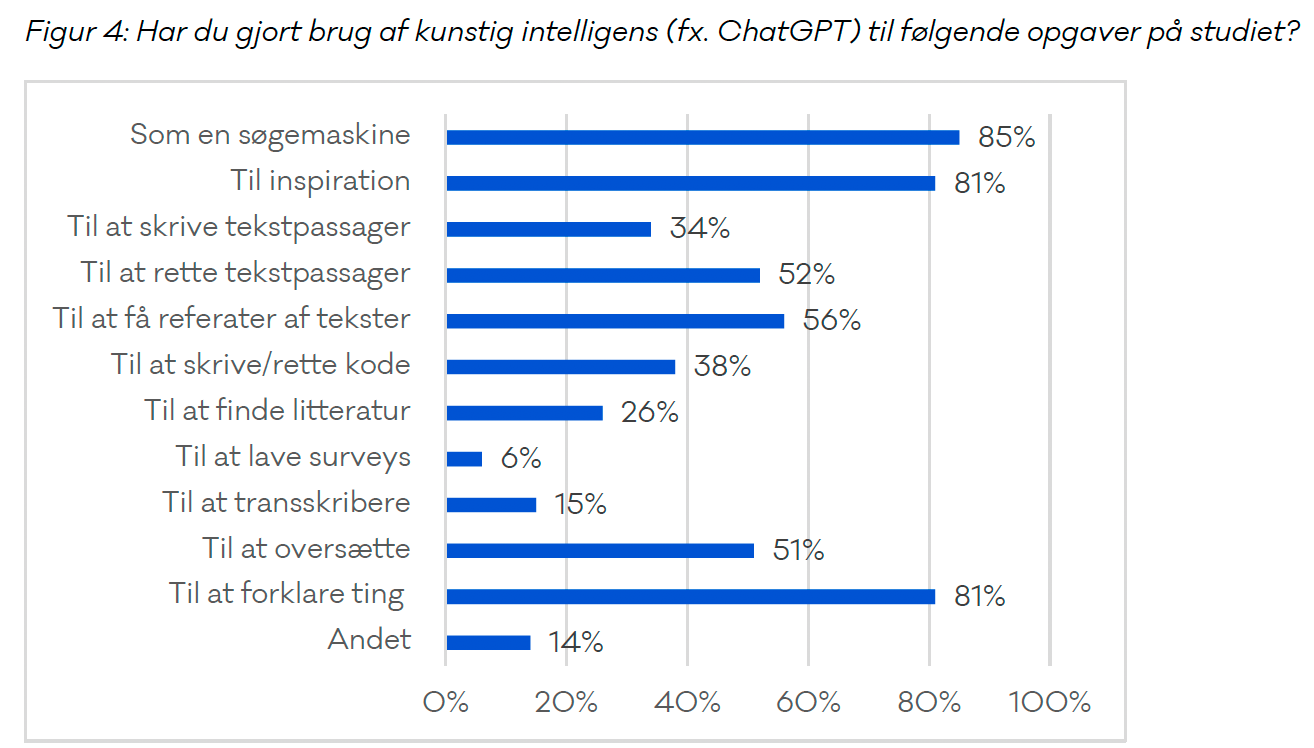

A survey by DJØF from October 2024 shows that 85% of the students surveyed had used the regular ChatGPT as a search engine. This survey was conducted before the launch of Search GPT, further emphasizing the points made in this article.

The Role of Educators in Guiding Students

We face a critical task in education: helping our students navigate this new and complex information landscape. We must assist them in developing the necessary skills to assess the quality of answers—whether they come from humans, generative artificial intelligence, traditional search engines, or sources like books and articles. Most importantly, we must enable them to choose the right information sources based on the nature of the task.

One key question these new AI search engines raised is the tension between synthesized and validated knowledge. By summarizing information from multiple sources and presenting it in an easily digestible format, these tools can give the impression of delivering authoritative knowledge. However, this synthesis carries significant risks: the inclusion of erroneous information (hallucinations), the loss of critical nuances, the omission of context, and the potential for unreliable sources to be given equal weight as high-quality ones. Combined with automation bias—the human tendency to trust machines—this creates a potentially dangerous cocktail.

Emily Bender, a professor of linguistics at the University of Washington, recently commented on AI search engines in a way that perfectly illustrates this challenge:

“Furthermore, a system that is right 95% of the time is arguably more dangerous than one right 50% of the time. People will be more likely to trust the output and less likely to fact-check the remaining 5%. Instead, you get an answer from a chatbot. Even if it is correct, you lose the opportunity for that growth in information literacy.”

As educators, we have a vital role in teaching students to distinguish between different types of knowledge, recognizing when information does not necessarily equate to expertise, and appreciating the value of solid, well-supported knowledge. We must teach them to resist the temptation of uncritically accepting synthesized AI answers and instead engage in the demanding yet essential process of independently searching for and evaluating the quality of sources.

AI Search Engines in a Philosophy of Science Perspective

From a philosophy of science perspective, the new AI-driven search tools raise fundamental questions about the nature of knowledge and scientific practice. Scientific knowledge is traditionally seen as the result of a careful, systematic process where hypotheses are tested, results are documented, and conclusions are subjected to critical peer review. Reliable news sources undergo journalistic processing and fact-checking and are held to ethical press guidelines. However, these principles are challenged when answers are generated by opaque algorithms that synthesize information in ways we do not fully understand.

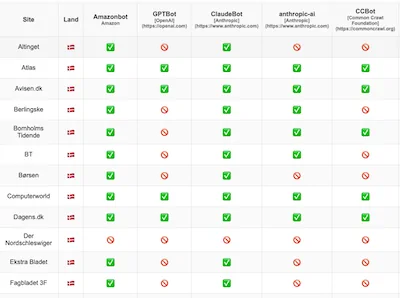

One particular issue with news sources is that many prominent and credible media outlets have blocked access to these AI search engines. A simple test reveals that no serious Danish news outlets appear as sources in search results! On viden.ai, we have developed a bot that checks which Danish newspapers block or allow various AI services access. The list, which is updated automatically, can be viewed here:

You can find information about which Danish news media are actively blocking AI services. Several media outlets in Denmark have taken steps to prevent their content from being used by AI systems without authorization.

A central challenge with many AI systems is their epistemic opacity. Although tools like ChatGPT Search, Google AI Search, and other AI-driven search engines provide source references, selecting, weighting, interpreting, and synthesizing these sources remain hidden. We cannot trace how conclusions are reached—an approach fundamentally at odds with scientific ideals of transparency and critical inquiry. If we cannot fully understand or replicate the process of generating an answer, how can we trust the validity of those answers?

These concerns become particularly pressing when considering the risk of AI models amplifying existing biases or misrepresenting misleading correlations as causal relationships. Additionally, in their effort to provide clear, unambiguous answers, AI systems may fail to convey the uncertainty and nuance that often define knowledge. Science rarely offers absolute truths; instead, it operates in probabilities, assumptions, caveats, and ongoing debates and disagreements.

If AI-generated responses present scientific conclusions as 100% definitive facts, they risk distorting the true nature of science. This could lead users to misunderstand scientific inquiry's inherent complexity and provisional nature, undermining their ability to engage with information critically.

Developing Critical AI Literacy and Information Competence

We must teach what constitutes valid knowledge and how to assess its quality. Students must learn to value transparency, embrace uncertainty, and see knowledge as an evolving dynamic process. It is crucial to foster a healthy skepticism toward any system claiming to offer quick, definitive, and timeless answers. Instead, we should empower students to engage directly with primary sources and academic discussions.

In light of these challenges, source criticism, information literacy, and technological understanding are becoming more critical. Our students require tools to navigate an increasingly complex information landscape where the boundaries between human-created and AI-generated knowledge are increasingly fluid. Rather than solely evaluating the credibility of individual sources, we must also teach students to scrutinize the processes underlying how information is synthesized and presented.

They should learn to ask questions such as:

- What criteria does this system use to select and prioritize sources?

- Are there potential biases embedded in the system’s algorithms?

- How can we verify the claims being made?

- Most importantly, is this even a source, or are we dealing with synthesized text?

We might need to teach students to view any response—regardless of its origin or perceived authority—as a hypothesis to be tested rather than as an established truth.

Additionally, we must help students understand when different types of information sources are appropriate. While synthesized AI responses can be helpful for quickly gaining an overview of a non-critical topic, they may fall short when a task demands in-depth analysis and understanding. Conversely, time constraints in certain situations might make traditional academic sources impractical, whereas AI-generated responses could serve as an acceptable compromise if the consequences are understood.

The Art of Asking the Right Questions

Being critical of sources involves considering their quality, relevance, and timeliness—whether they are current and up-to-date or potentially outdated. But how can we determine whether an answer is perfect? This question is relevant to AI-driven searches and applies whenever we seek information to answer a question.

Key aspects to examine include whether the answer directly addresses the question posed—is it even relevant? Is the answer well-supported, and does it present a balanced, nuanced treatment of the subject, or does it favor specific perspectives at the expense of others? Does it rely on solid logical reasoning and empirical evidence, or does it contain gaps, leaps in logic, or circular arguments? Does it acknowledge areas of uncertainty, debate, or conflicting interpretations, or does it present complex issues as simple and unequivocal?

Critical evaluation is not just about assessing the answers we receive—it also involves asking the right questions in the first place. The effective use of generative artificial intelligence and various search engines, whether AI-driven or traditional, depends on the ability to craft straightforward, specific questions suited to the particular search method. A too broad or vague question is likely to yield a superficial or confusing answer. At the same time, a question that is too narrow or leading may produce a response that merely confirms the questioner’s existing assumptions.

When asking another person a question, an unclear question often prompts clarifying responses, such as, “What do you mean?” or “I’m not sure I understand…”. A language model, however, will generate an answer based on the phrasing, which may result in incorrect or imprecise information. While it is possible to ask an AI search engine follow-up questions, recognizing the need for clarification can be challenging for students who feel uncertain or lack confidence in their subject knowledge.

To address this, we must teach our students strategies for effective question formulation tailored to different information sources. These strategies include breaking complex questions into their components, identifying subject-specific key terms, considering the question from multiple perspectives, and iteratively refining and improving the question based on the responses generated. By mastering the art of asking good questions, students can become more effective users of these technologies, leveraging them as powerful tools for inquiry and learning. Moreover, posing practical questions requires a solid foundational understanding of the explored field.

Conclusion

We should accept AI search tools altogether; instead, we should focus on developing a strategic and, most importantly, context-sensitive approach to their use. We can enhance information literacy and critical thinking by reflecting on the strengths and limitations of different information sources and making thoughtful choices based on the specific task.

Through education, we must foster “critical AI literacy” and, perhaps more importantly, robust information literacy. Students must learn to use AI technologies effectively and understand their underlying mechanisms, ethical implications, and potential biases. They need to evaluate AI-generated information critically, use AI as a reflective tool for learning and problem-solving, and apply it responsibly in a social context. Most importantly, they must learn when AI tools are appropriate and especially when they should be avoided. In short, we must educate informed, critical, and ethical users of diverse information sources.

Sources:

Envisioning Information Access Systems: What Makes for Good Tools and a Healthy Web? Chirag Shah and Emily M. Bender:

https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3649468

https://buttondown.com/maiht3k/archive/information-literacy-and-chatbots-as-search/