In the latest article, I introduced the concept of "professional grief" and the challenges educators face when encountering artificial intelligence. If you haven't read it, you can find it here:

In this article, the second of seven, I explore the first dimension: how artificial intelligence affects and challenges the teacher's professional identity. I wrote these articles based on my many conversations with high school teachers during our presentations. Therefore, you should view the entire article series as a testimony of these conversations and my attempt to contextualize it within well-known theoretical frameworks.

Artificial intelligence and professional identity

For many teachers, their subject and teaching practice are closely linked to their identity and self-understanding. I frequently encounter this connection when conversing with individual teachers during our presentations, especially observing their passion for the subject and the student's academic understanding. This deep connection between subject, practice, and identity forms the basis for many teachers' professional engagement and effectiveness. But when new technology like artificial intelligence can suddenly take over or revolutionize parts of this practice, it can shake the very foundation of one's professional identity.

According to Poulsen and Meier's research (2022), introducing new technology can lead to teachers experiencing changes or loss of work tasks and processes that have otherwise been a central part of their professional activities. An identity crisis can emerge, forcing teachers to redefine what being a teacher in their subject means.

In 1984, psychologist Craig Brod introduced the term "technostress," which describes the modern adaptation disease that arises when the individual fails to handle new technologies healthily (Chang et al., 2024). Technostress can arise in teaching in many ways. Some teachers feel overwhelmed and inadequate in the face of constant demands to keep up with technological developments. Others experience a real fear of being made redundant by intelligent systems.

Teachers may feel overwhelmed and overloaded by constant demands to keep up with technological developments. Many describe a feeling of inadequacy and do not believe they possess the necessary skills to integrate technology effectively into teaching. I also meet some who fear redundancy, where teachers are concerned about whether intelligent systems can replace them entirely or partially.

Here, we should perhaps be particularly aware of the exaggerated hype around the many possibilities of technology. Tech giants seeking investors or companies that claim to have found the golden solution for the future of education have created this hype. When we see the video where ChatGPT acts as a tutor for Sal Khan's (the founder of Khan Academy) son, and the language model speaks and instructs, it is just a short instructional sequence in a controlled experiment that shows how students can use an assistive tool. However, teaching involves much more than this showcase, and it would be downgrading our entire education system if we thought that AI would take over a dynamic and unpredictable teaching space.

Finally, time pressure is a significant factor, as teachers experience not having enough time to learn and implement new AI tools alongside their work tasks.

But as Chang et al. (2024) point out, technostress is not just a question of feeling overwhelmed or being afraid of being replaced. Technological stress can take two forms: a positive challenge that motivates us to learn and develop professionally (challenge stressors) or a direct obstacle that blocks our work and arouses frustration (hindrance stressors).

In my teaching, I have experienced both sides of technostress. On the one hand, the encounter with AI tools like ChatGPT has allowed me to rethink my teaching and experiment with new, creative assignment types - which gives me energy. But I have also felt the overwhelming feeling of suddenly having to familiarize myself with a completely new technology on top of all my other tasks. Here, I have experienced a nagging doubt about whether I have the right skills to use AI meaningfully in my teaching. How much preparation and teaching time can I dedicate to an area not yet part of the student's exam curriculum?

The experience of loss of control and professional grief

The loss of professionalism to artificial intelligence can deal a hard blow to teachers' professional self-understanding, regardless of whether new technology is introduced gradually or suddenly. What are we as teachers if we are not experts in our subject and disseminators of knowledge? What is our right to exist if a chatbot can suddenly give feedback, tailor teaching, and answer questions at least as well as we can?

Guldin (2018) describes in his book "Grief" how losing a central part of one's life - whether a body part, a loved one, or an identity - can trigger a deep existential crisis and a need to find new meaning. In the same way, the loss of familiar teaching tasks and roles to AI can feel like a loss of a part of oneself. Suddenly, you are no longer indispensable. AI threatens your status, relationships, and experience of control. Professional grief can manifest itself as identity confusion, anger, paralysis - or perhaps even depression and meaninglessness.

Thus, professional grief and loss of identity in the encounter with AI are psychological realities for many teachers. But how can we better understand the different phases of this process and the challenges and opportunities associated with each of them? William Bridges' Transition Model can offer a helpful perspective on this change.

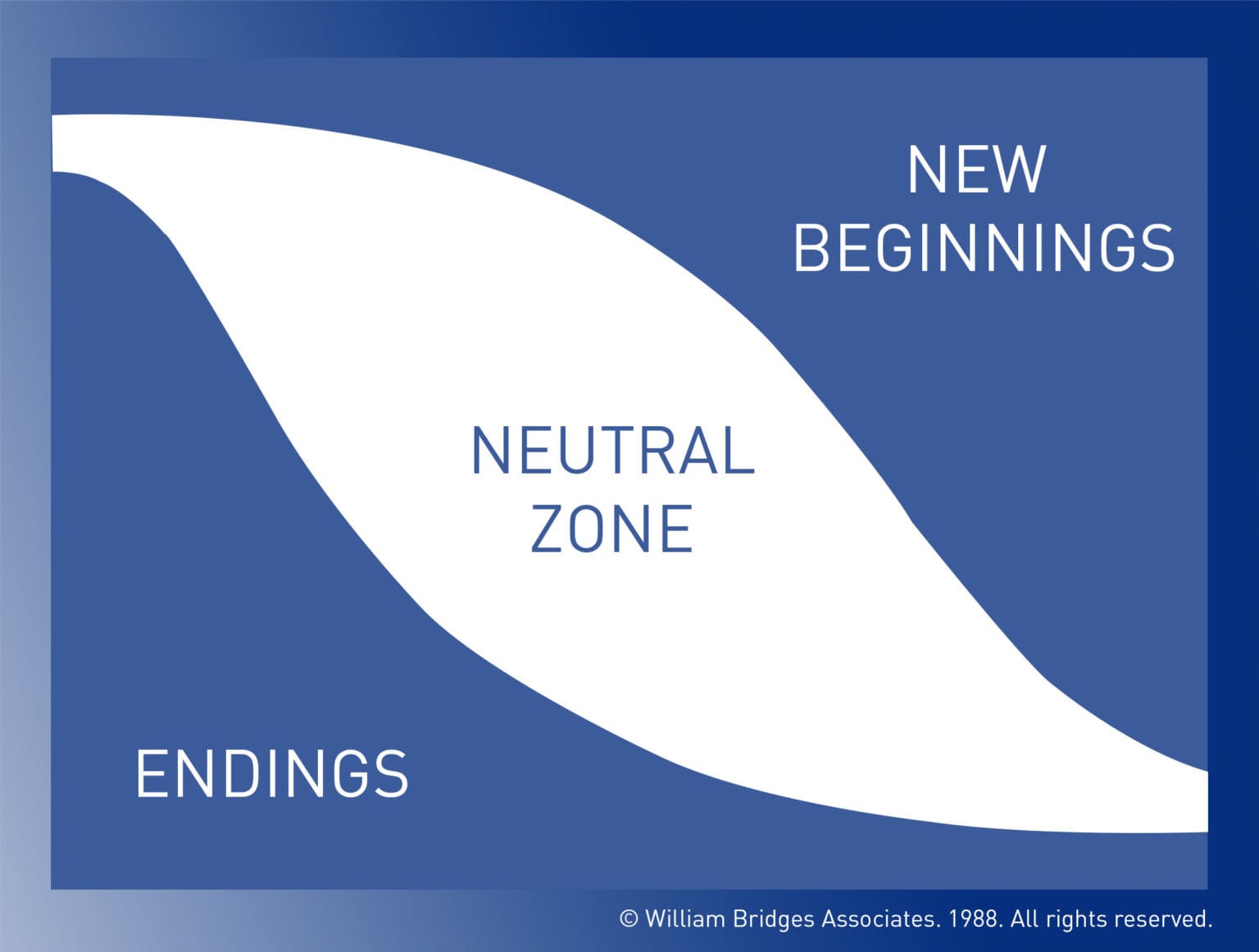

Bridges' Transition Model and the three phases of change

According to William Bridges' Transition Model, all teachers undergo three phases when new technology is introduced in teaching - ending, neutral zone, and new beginning. (Bridges & Bridges, 2017).

In the ending phase, teachers may have to say goodbye to familiar routines, materials, or teaching methods developed through many years of experience. Professional practice and professional knowledge building are attached to the individual teacher. When one's didactic approach or professional expertise is suddenly challenged by artificial intelligence, it can arouse feelings of loss, anger, and confusion. Here, the teacher must recognize and process these feelings to let go and move on.

In the neutral zone, teachers find themselves in a limbo between the old and the new. They are no longer what they were but are not yet entirely comfortable in their new roles and relationships with AI. Many will experience uncertainty, doubt, and frustration as they experiment with integrating the latest tools into teaching. How can AI become a meaningful part of their pedagogical practice? What does it mean for the relationship with the students and their own identity as a subject person? What does it mean when students always have an AI available? In all the confusion, however, there is also a breeding ground for creativity and innovation - if one dares to explore the unknown.

Finally, the teacher reaches a new beginning, where AI no longer feels foreign but gradually integrates into the teaching. Here, it is about strengthening the latest skills, forms of collaboration, and teaching courses that have developed along the way. It is also about rediscovering one's professional identity and pride in a new reality - perhaps even with a deeper understanding of what it means to facilitate learning in a digital age. Artificial intelligence is no longer a threat but an integrated part of their professional practice and self-understanding.

Using Bridges' model, we can perhaps better understand teachers' challenges and opportunities. Technostress and professional grief in encounters with AI are complex challenges for many teachers.

The teacher's technical self-efficacy as a key to mastery

In the encounter with AI-driven technostress, the teacher's technical self-efficacy - the belief in one's ability to master the technology - plays a crucial role. Albert Bandura, the originator of the concept of self-efficacy, describes it as a central mechanism in human agency and motivation (Bandura, 2012). When we believe in our ability to influence our surroundings and achieve results, we become more likely to take on challenges and show perseverance.

In a teaching context characterized by artificial intelligence, high technical self-efficacy can function as a shield against negative stress. Teachers with confidence in their technical skills will be more inclined to see AI as an exciting opportunity for development - even when it requires a great effort to learn something new. They meet the challenges with a positive, problem-solving approach, seeing mistakes as stepping stones towards mastery. Bandura notes that they have a "robust perception of self-efficacy" that helps them maintain engagement and well-being under pressure (Bandura, 2012, p. 19).

Conversely, teachers with low technical self-efficacy risk being overwhelmed and paralyzed by technological upheaval. Each new challenge confirms their fear of inadequacy and activates catastrophic thoughts about becoming redundant. Low technical self-efficacy can lead to avoidance behavior, reduced work effort, and outright resistance to change.

So, how can schools strengthen teachers' technical self-efficacy? Here, Bandura offers a range of tools, including mastery experiences, role models, and verbal persuasion. It's about designing a work environment that provides supportive frameworks for experimenting with AI, gaining successful experiences, and learning from skilled colleagues. Here, a well-designed combination of courses, technical support, and psychological safety can equip teachers to embrace future technology with confidence and curiosity - even when it's complicated.

Conclusion

Finding oneself and professionalism in an AI-influenced teaching world can be complex and demanding. For some teachers, it's about reflecting on their psychological reactions to the technology and actively trying to create meaning for themselves and their students in the new reality. But it is essential to recognize that not everyone has the resources, energy, or motivation to embark on that exercise—especially during a busy and changing everyday life.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to dealing with AI's identity and emotional challenges. Some may need more time, support, or competency development to find a foothold, while others will dive headfirst into the experiments. We need to meet teachers where they are and recognize the diverse reactions and needs that can arise in their encounters with AI technologies.

Regardless of the approach, however, it is crucial that teachers actively relate to what it means to be a good teacher in a digital age—both for their self-understanding and to offer students meaningful and contemporary teaching.

In the following article in this series, I will explore how AI specifically challenges teachers' autonomy. How can we maintain our professional self-determination and agency if we collaborate with self-learning algorithms? Students using artificial intelligence to challenge the teaching in the background can evoke another uncomfortable feeling of powerlessness.

Sources

Bridges, W., & Bridges, S. (2017). Managing transitions. Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Bandura, A. (2012). Self-efficacy. Kognition og pædagogik, 22(83).

Chang, P.-C., Zhang, W., Cai, Q., & Guo, H. (2024). Does AI-driven technostress promote or hinder employees’ intention to adopt artificial intelligence? A moderated mediation model of affective reactions and technical self-efficacy. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 17, 413–427. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S441444

Guldin, M.-B. (2018). Sorg. Aarhus University Press.

Poulsen, J. S., & Meier, D. S. (2022). Sammen om ny teknologi - Sådan får vi det bedste ud af de digitale muligheder (O. Jørgensen (red.)). Fremfærd. https://vpt.dk/sites/default/files/2022-05/Fremf%C3%A6rd%20Sammen%20om%20ny%20teknologi.pdf

Walker, T. (2023, december 3). “My Empathy Felt Drained”: Educators Struggle With Compassion Fatigue. National Education Association (NEA). https://www.nea.org/nea-today/all-news-articles/compassion-fatigue-teachers